If you couldn’t tell by the name of this page, 𝘢𝘵𝘵𝘢𝘤𝘩𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 is something we look at a lot here.

Attachment is the emotional roadmap we use when we feel disconnected from someone else. It’s how we find our way back to safety—how we reach, respond, and repair when closeness feels uncertain. Experts say that roadmap is mostly written by the time we’re two years old. Before we can even speak, we’re already learning what it feels like to be held, comforted, or ignored… and those early patterns shape how we seek connection for the rest of our lives.

That includes how we relate to God.

In 𝘈𝘵𝘵𝘢𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘎𝘰𝘥, Krispin Mayfield talks about how we sometimes stumble into something beautiful with God—only to wonder later why the connection feels so unstable. So we try harder. We repeat the steps that seemed to work before. We draw new “maps” made of confession, worship, and discipline, hoping to feel close again. But the pattern never stays the same, and we’re left wondering what we did wrong.

It’s exhausting. And underneath it all, many of us quietly assume what Mayfield put into words: “I presumed something was wrong with me and my best bet was to try to be a better me, someone more worthy of God’s nearness.”—hoping that God might actually “like” us.

But the truth is, the Gospel itself is a depiction of God’s work to repair the rupture caused by sin.

From the garden to the cross, God has always been the One moving toward us—seeking, calling, embracing. When humans hid in shame, God came walking. When we ran, He pursued. When we failed, He drew near again.

Attachment science helps us name our patterns of reaching out; the Gospel shows us the God who always reaches back.

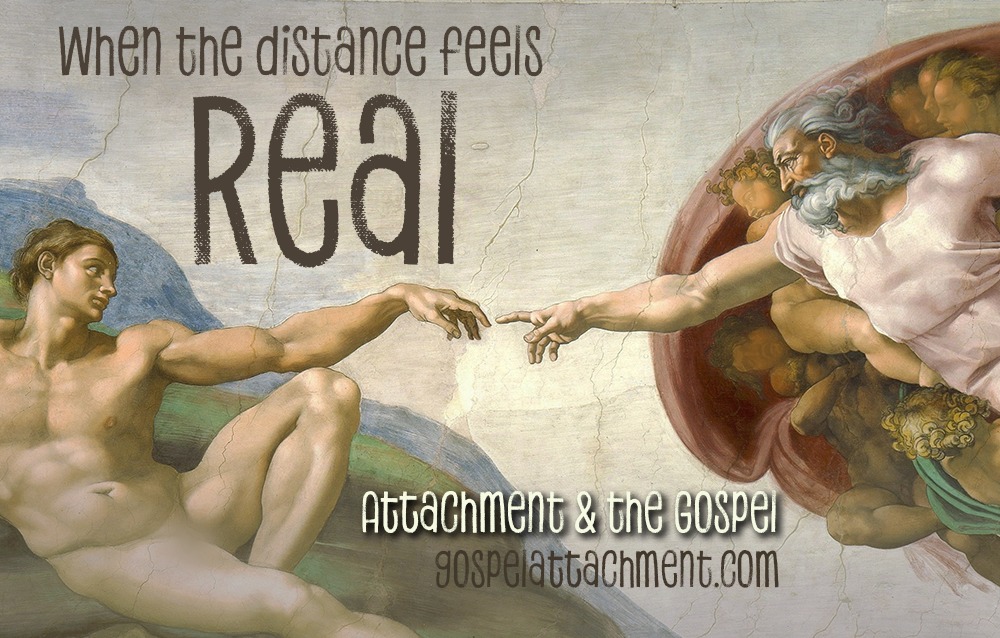

Recently, it was brought to my attention that in Michelangelo’s 𝘊𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 𝘈𝘥𝘢𝘮, God is depicted as if in motion—His hair and beard blown back by the wind—as He reaches toward Adam with His arm fully extended. Adam, by contrast, sits back and lifts his hand lazily, his finger bent just short of touching God’s.

That tiny gap between the fingers has always fascinated art historians, but it also preaches. God is reaching with all His might, straining toward His creation, but Adam hasn’t yet responded. It’s not that God is distant; it’s that the human heart hesitates.

It’s a perfect picture of grace. God has already done everything to bridge the distance. But we still have to be open to the relationship being repaired—to reach back, even slightly.

And that reach—small as it may seem—requires vulnerability.

To let God near again.

To risk being seen, known, and loved in the places we’ve tried hardest to hide.

Because the God who reached toward Adam is still reaching toward us.

Leave a Reply